THREE-TOED WOODPECKER (Picoides tridactylus) Pic tridactyle

Summary

A rather discrete woodpecker of sub-alpine forests, not easy to find. It has an interesting way of life, specialising on bark beetles in spruce forests. It has a call very similar to a Great Spotted Woodpeckers and this article explains why, and how to identify the call.

from Cramp etal: Birds of the Western Palearctic

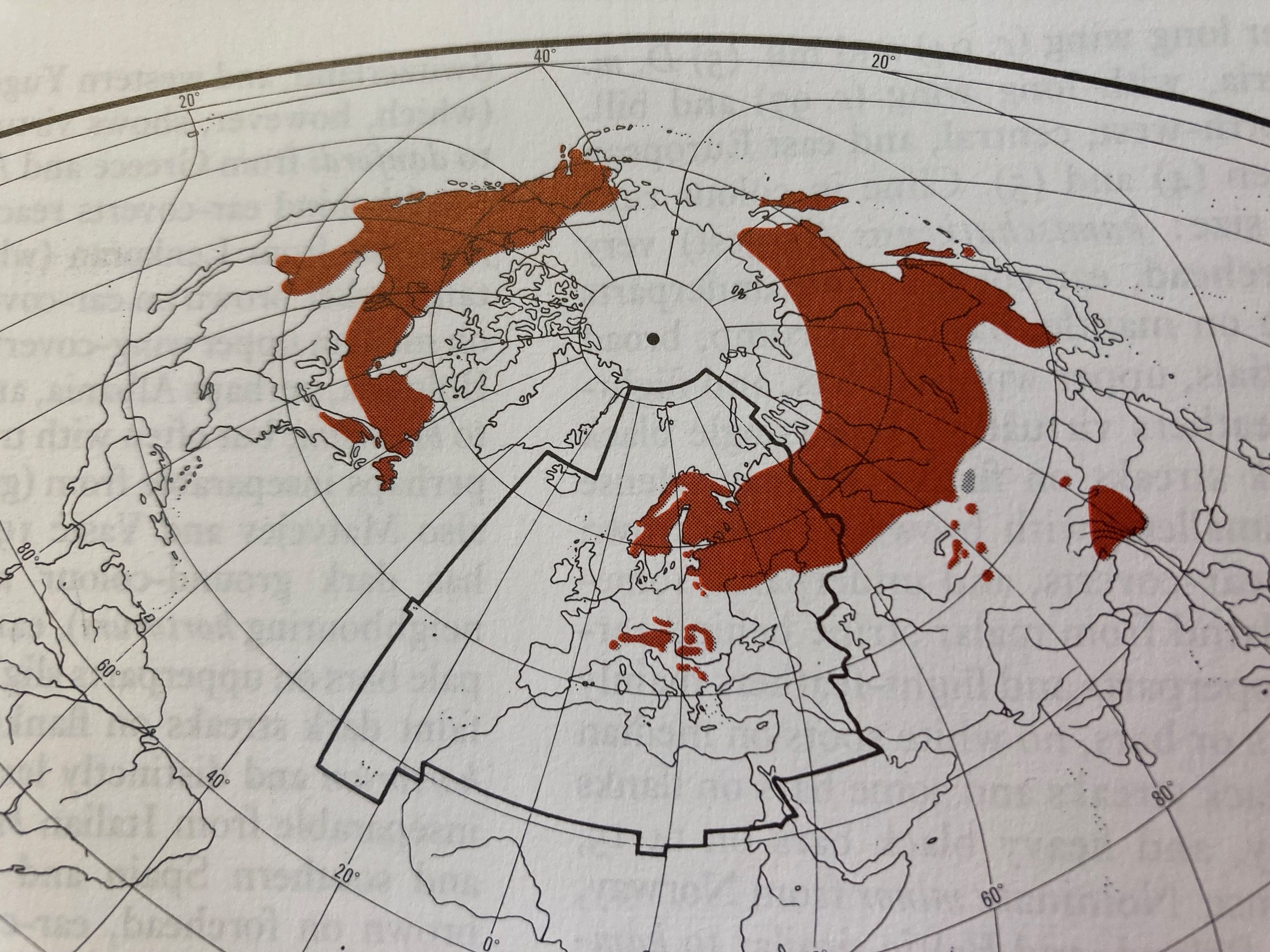

This is an interesting species which, as the name implies, has only three toes (two facing forward and one back). This is unique among European Woodpeckers, but there are others like this elsewhere in the world. The species extends around the globe in the boreal region of the north (upper map) and some authorities regard the Eurasian and American birds as different species - but we won’t go into that here!

From: IUCN through Wikipedia

The lower map shows more detail for the European group. You can see that the Western Switzerland population, where my recordings were made, is right at the limit of the distribution of the alpine subspecies Picoides tridactylus alpinus. In fact, the small group in the Western Jura that I have followed, only became established within the last 20 years. The fragmented nature of this southern group is probably due to glacial history and human use of forests.

Spruce bark beetle, larvae, pupae and adults are all eaten

This is a woodpecker that prefers old growth, mature, spruce forests in the sub-alpine zone, between 1000-2000m above sea level and it specialises in eating bark beetles (bostryche). These beetles burrow under the bark of trees damaging the phloem vessels and introducing fungal diseases. Outbreaks of bark beetles occur in trees damaged by storms or are stressed by acid rain or drought induced climate change. Infested dead and dying trees are the ones favoured by Three-toed Woodpeckers and it has been found the best habitat for this species is a forest with a minimum of 5% of standing trees which are dead or dying (Butler et al 2004).

Three-toed Woodpecker habitat

Typical damage from accessing bark beetles

The Three-toed Woodepcker cannot be described as a common bird due to its habitat requirements. Even in the right habitat it is not easily encountered. Gorman (2004) describes it as “unobtrusive and often elusive”. It is tolerant of human presence, and I have observed it from only a few meters away, but it will quietly hide behind the trunk of a tree and, being generally a rather silent bird, its existence is very discrete.

CALLING

To complicate matters, when it does call it is easily confused with the slightly larger and much more vocal Great Spotted Woodpecker, however the call is somewhat softer and does not carry as far.

I have found the similarity between Three-toed and Great Spotted Woodpecker calls quite confusing, and wanted to understand them better, and try to learn to distinguish them in the field. Below is a comparison of four calls from each, Three-toed first and Great Spotted second :

Comparison of two woodpecker calls: Four calls of Three-toed Woodpecker followed by four calls of Great Spotted Woodpecker

Two things are immediately obvious: the Three-toed note is lower pitched with the peak frequency around 2kHz, whereas the peak energy in Great Spotted is around 4.8kHz. Also the Three-toed has a softer, more “squidgy” sound, a sort of “chup” note, whereas the the Great Spotted has a more clipped, penetrating, sharper “kik” quality. I was then interested in what may cause this difference in the “timbre” of the two.

Single notes of the Three-toed (left) and Great Spotted (right) Woodpeckers and the measures taken (red arrow)

In the above sonogramme, the Three-toed note looks like a very narrow inverted “V”. If we zoom in a single call, it shows that both species have an inverted “V” shape. The Three-toed “V” has a wider base which tells us that the delivery of the note takes more time. I measured the time taken for each note to be delivered (the red arrow in the figures on the right). In a sample of 13 Three-toed calls the average delivery time was 48.08 milliseconds +/- 3.77 (s.d.); the same measurement on 19 Great Spotted calls was 30.63 milliseconds +/2.99 (s.d.). So the Three-toed takes 57% more time to deliver each note than the Great Spotted.

I suggest that this slower note delivery, coupled with the lower frequency, underlies the characteristic “softer” feel to the call of the Three-toed. But it is not easy to separate them: and the real challenge is detecting this with our inadequate human ears, in the forest, in isolation, when you can’t see the bird!

DRUMMING

But of course calling is not the only way that woodpeckers advertise their presence. Like most others, the Three-toed Woodpecker also drums on a suitable surface. The bird is a smallish (slightly smaller than Great Spotted) but stocky creature. It has a thick muscular neck and the drumming is quite characteristic. It is usually loud, made from a high perch, and has a very deliberate rhythm to it, slower and shorter than Great Spotted, and somehow clearer. It has been compared with a burst of fire from a machine gun.

They excavate a new nest hole each year

They drum mostly in the winter and spring. Both sexes drum but the male more than the female (Cramp etal 1985; Gorman 2004). If you listen again carefully (to the 2nd, 3rd and 4th sequence) there is another bird in the background that may be responding. This recording was made in mid-October and it shows the natural spacing of drums 30-40 secs apart. The four sequences averaged 21.75 strikes over 1.37 secs (15.88 strikes per second), this is very close to the rate reported by others (Cramp etal 1985; Gorman 2004). Each sequence starts with a low amplitude, quickly building to a plateau before tailing off in the last few strikes - see below:

Three-toed Woodpecker male (Daniil Komov on Unsplash)

Those are the major sounds you are likely to hear from these birds, but it is not the only ones by any means. The video below shows just one minute of events, shortly after dawn, when I had placed my microphones near a tree with several nest holes (this species excavates a new nest hole each year).

It starts with the call of a cuckoo echoing across the valley, and many thrushes, robins, finches and others singing in the background. There is a flutter of wings, and at 4 secs the woodpecker calls 7 times. It then starts to feed at 14 secs and you can hear its tapping and excavating sounds, at 24 secs there is a flutter of wings and suddenly loud drumming at 28 secs. I think the other one of the pair flew in because there then begins some very small “squeaks” and “sucking” noises as if the pair were interacting at intimate close quarters. Finally at least one birds flies off at 55 secs - listen out for the slight whistle from the wings, something I have noticed in this species before.

You can read how I managed to catch some of these sounds and listen to more from this bird in the Sound Diary.